Compiling With Constraints

There are lots of interesting little subproblems in compilation like instruction selection, register allocation and instruction scheduling. These can be expressed in declarative interlinked way to constraint solvers.

I’ve been fiddling with probably 6 iterations of using constraint solvers for compiler backends over the last 3 years and never written a blog post on it. This is long over due, and still highly imperfect. I have found this post only gets harder to write and my standards rise. Write early, write often.

Basic Idea

Register allocation is the backend problem most obviously castable as a constraint problem. It is often described as a variant of graph coloring (there are nuances like coalescing). Graph coloring selects a color for each vertex in a graph such that no edge connects two nodes of the same color.

Here’s a toy implementation over a single SSA block using z3. Traversing backwards through a block is a useful trick to analyze liveness while you’re also building constraint.

During this collection, you can also emit any constraints that are opcode specific. Some instructions like the mul instruction in x86 do not work on every kind of register. You can also collect up specific objective functions, for example biasing mov to go between the same registers. Spilling to the stack can be modelled by pseudo registers that you put a lot of weight on. Requiring the input or output parameters follow any calling convention is again a simple extra constraint.

Multiple blocks can be linked together in the same constraint solve by sharing variables. This may require packing in extra mov instructions between blocks to keep the problem solvable in general. See this paper for more

from typing import List, Tuple

from collections import namedtuple

from dataclasses import dataclass

import z3

# using an enumlike alegrbaic datatype is probably the cleanest way to model this

RegSort = z3.Datatype("Register")

for r in "R0 R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 R6 R7".split():

RegSort.declare(r)

RegSort = RegSort.create()

x,y,z,w = z3.Consts("x y z w", RegSort)

# Types. I'm not particularly enforcing them.

OpCode = str

Operation = tuple[OpCode, "RegSort", List["RegSort"]]

Prog = List[Operation]

prog = [

("mov", z, [y]),

("add", x, [y, z]),

("sub", w, [y, z]),

("dummy_out", None, [x,w]) # a dummy node to put demand on output

]

def compile(prog):

"""Get the constraints out of a program"""

live = set()

constraints = []

objective = []

for insn, (op, out, in_ops) in enumerate(reversed(prog)): # backwards to collect up liveness

print(op, out, in_ops, live)

if out != None:

live.discard(out) # assignment means variable is no long defined

live.update(in_ops)

constraints.append(z3.Distinct(live))

if op == "mov": #it's nice to fuse out mov

objective.append(out == in_ops[0])

return constraints, objective, live

constraints, objective, live_entry = compile(prog)

s = z3.Solver() # could use z3 optimize api.

s.add(constraints)

print(s)

s.check()

s.model()

dummy_out None [x, w] set()

sub w [y, z] {w, x}

add x [y, z] {z, y, x}

mov z [y] {z, y}

[w != x, Distinct(z, y, x), z != y, Distinct(y)]

[w = R0, z = R2, y = R0, x = R1]

def build(prog, sol):

"""Fill in a program from a solution."""

return [(op, sol[out] if out != None else None, [sol[arg] for arg in in_ops]) for op, out, in_ops in prog]

def pp(prog):

"""Pretty print a program."""

for op, out, in_ops in prog:

print(op, ", ".join(map(str, [out] + in_ops)))

prog_reg = build(prog,s.model())

pp(prog_reg)

mov R2, R0

add R1, R0, R2

sub R0, R0, R2

dummy_out None, R1, R0

Why?

One might think the advantage of compiling with constraints is getting perfectly optimized solutions. I have found this to not be the case. Heuristic solutions to these problems are fast and effective.

The advantage to compiling with constraints is that it short, declarative and rapidly flexible.

It also is another attack on the phase ordering problem, similar to the pitch for egraphs. The phase ordering problem is that these compiler phases are interlinked, so there are uncomfortable compromises made in serializing them.

Mainly for me its just fun though. I like solvers.

Distinction To Superoptimization

Superoptimization as I’ll define it today is taking the semantics of assembly instructions, the semantics of your host program, making the constraint that they match and tossing it into a solver. This is vastly over simplified. Any even remotely pragmatic approach prunes the search space significantly using domain specific techniques.

The difference between this and compiling with constraints is that compilation with constraints does not take a deep semantical perspective. The deep semantics are encoded in the instruction selection table, the generation of which I am not commenting on.

Compiling with constraints is largely concerned only with the dependency relationship of operands and instructions. This is a more tractable abstraction than the full instruction semantics. It also can be viewed as taking a traditional compiler pipeline and making it more declarative.

Superoptimization traditionally scales very poorly. Compiling with constraints could feasibly be done at a much larger more practical scale as the Unison compiler showed.

VIBES and Minizinc

I first started on the VIBES project https://github.com/draperlaboratory/VIBES . The hypothesis there was that binary patching requires unusual constraints and that superoptimization like abilities may make the difference between patching in place or requiring detours. These two cases are very different tiers of complexity and error-proneness. In micropatching we are compiling very small program fragments, for which the slowness of constraint compiling is not an issue.

This proposal was highly inspired by the Unison compiler (not the distributed system one). You can find our minizinc model here https://github.com/draperlaboratory/VIBES/blob/main/resources/minizinc/model.mzn . It is a simplified form of the constraint model from Unison.

A few comments to help explain:

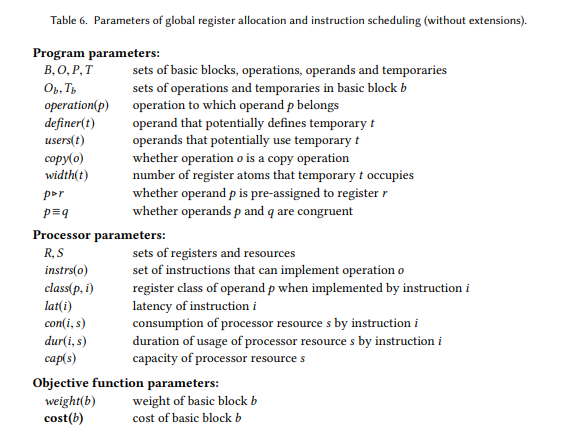

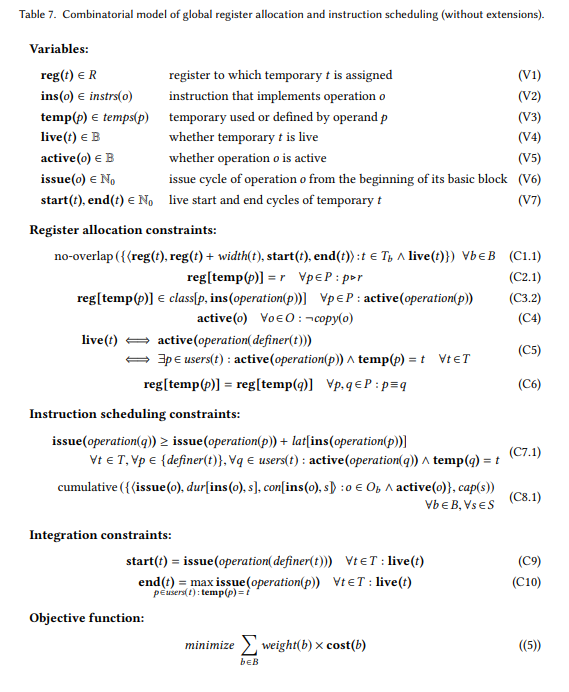

The paper “Combinatorial Register Allocation and Instruction Scheduling” was crucial. In particular append A is a very useful artifact.

These are the solver variables of our model. reg is a mapping from temporaries to possible registers. issue is a mapping from operation to issue cycle. The rest of the bits are constrained to make sense following the solution of these variables.

%% ---------------------------------------------------------------

%% VARIABLES

%% ---------------------------------------------------------------

array[temp_t] of var reg_t : reg;

array[operation_t] of var opcode_t : opcode;

array[operand_t] of var temp_t : temp;

array[temp_t] of var bool : live;

array[operation_t] of var bool : active;

array[operation_t] of var 0..MAXC : issue; % maybe make these ranges. I could see a good argument for that

array[temp_t] of var 0..MAXC : start_cycle;

array[temp_t] of var 0..MAXC : end_cycle;

Here is an example constraint. They map back to the table from the Unison paper.

% C7.1 The issue cycle of operations that define temporaries must be before all

% active operations that use that temporary

constraint forall (t in temp_t)(

let {operand_t : p = definer[t]} in

forall(q in users[t] where active[operand_operation[q]] /\ temp[q] == t)(

let {operation_t : u = operand_operation[q]} in

let {operation_t : d = operand_operation[p]} in

issue[u] >= issue[d] + latency[opcode[d]]

)

);

In the end I don’t believe the hypothesis that this complexity was needed for micropatching was born out and we would have been better served by a more traditional compiler architecture. We became ensnared in the implementation issues of talking to the constraint solver and the concepts of the model were too rigid and complicated to explain easily to others or modify when inevitable surprises popped up. Serialization to and from minizinc was very painful. That these data structures were not easily hand editable or all that readable (they were human readable json, but gobs of complicated json) was a huge impediment to development and debugging when my bandwidth was already strapped. Live and learn.

It has been asked before why we didn’t use Z3 as it has great bindings and we already used it elsewhere. The answer is we were sticking close to the Unison design (we actually initially wanted to literally reuse their model, but it was completely incomprehensible to me after some weeks of trying to decrypt it). There is a general question of when to use CSP, MIP, SAT, ASP, or SMT. I have never seen a good answer. This is a good research question that someone should attack. My heuristic is that if the community in question targets problems similar ot yours, try that one. CSP, MIP and ASP are better for optimization style problems as compared to satisfaction.

One thing not fully realized was a simplification of the model to get rid of the distinction between temporaries and operands. This subtle conceptual distinction caused a lot of communication issues amongst the team. I think with the ability to have multiple possible operations overlapping means this could be factored out.

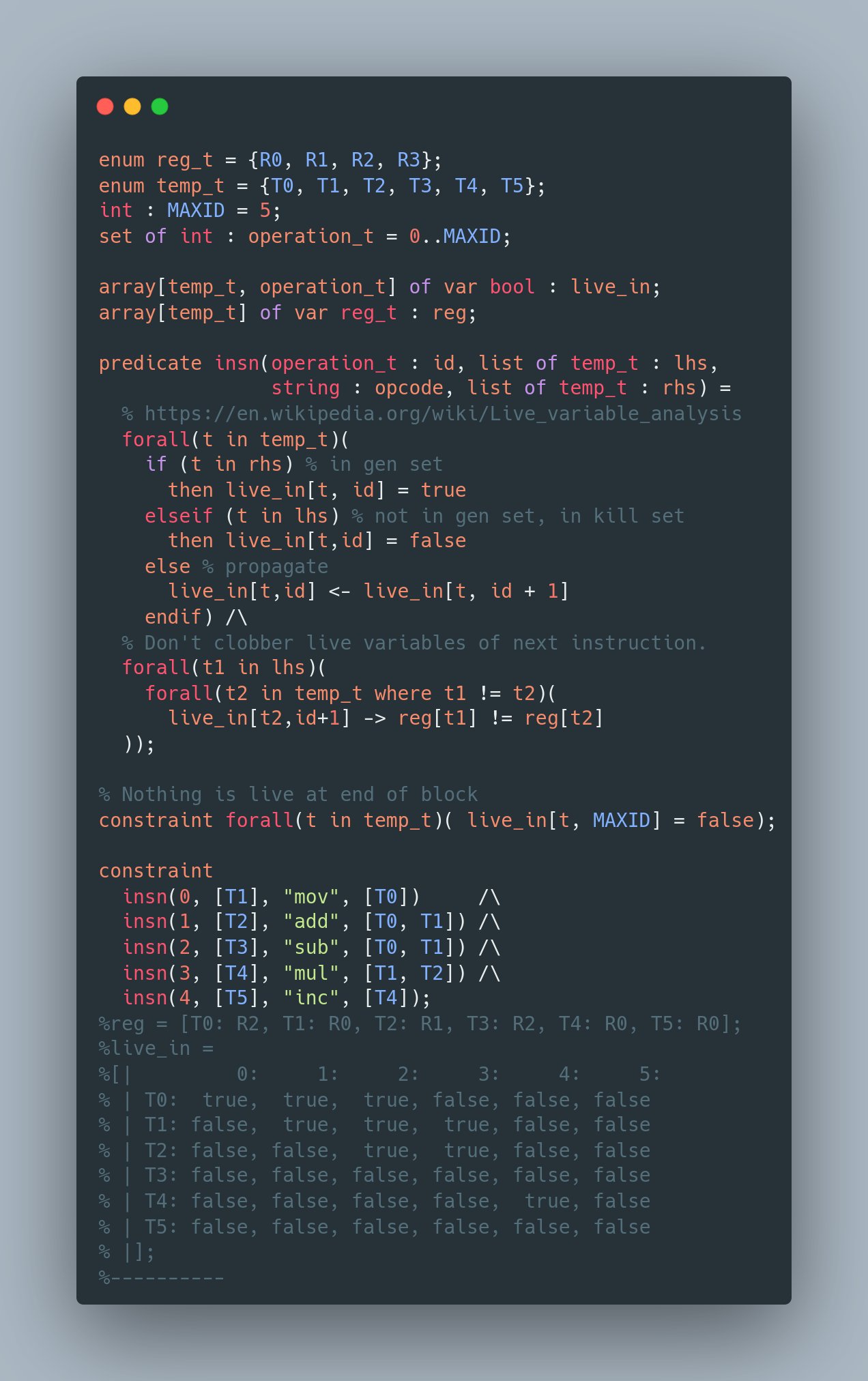

A not fully explored alternative was using a shallow embedding instead to encode the problem over to minizinc. This may have solved the pain that serialization caused us. Minizinc does not have good support for syntax trees as objects. However, it does support functions. So the idea was that instead of serializing to a pile of arrays, instead one can pretty print a program that looks like a relational representation of the program. This representation is immediately interpreted to constraint in the finally tagless style using minizinc function definitions.

I had a mini version of this in this tweet https://x.com/SandMouth/status/1530331356466712578?s=20

enum reg_t = {R0, R1, R2, R3};

enum temp_t = {T0, T1, T2, T3, T4, T5};

int : MAXID = 5;

set of int : operation_t = 0..MAXID;

array[temp_t, operation_t] of var bool : live_in;

array[temp_t] of var reg_t : reg;

predicate insn(operation_t : id, list of temp_t : lhs, string : opcode, list of temp_t : rhs) =

% https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Live_variable_analysis

forall(t in temp_t)(

if (t in rhs) % in gen set

then live_in[t, id] = true

elseif (t in lhs) % not in gen set, in kill set

then live_in[t,id] = false

else % propagate

live_in[t,id] <- live_in[t, id + 1]

endif) /\

% Assignments need to go to different registers than live variables of next instruction.

forall(t1 in lhs)(

forall(t2 in temp_t where t1 != t2)(

live_in[t2,id+1] -> reg[t1] != reg[t2]

));

% Nothing is live at end of block

constraint forall(t in temp_t)( live_in[t, MAXID] = false);

constraint

insn(0, [T1], "mov", [T0]) /\

insn(1, [T2], "add", [T0, T1]) /\

insn(2, [T3], "sub", [T0, T1]) /\

insn(3, [T4], "mul", [T1, T2]) /\

insn(4, [T5], "inc", [T4]);

%reg = [T0: R2, T1: R0, T2: R1, T3: R2, T4: R0, T5: R0];

%live_in =

%[| 0: 1: 2: 3: 4: 5:

% | T0: true, true, true, false, false, false

% | T1: false, true, true, true, false, false

% | T2: false, false, true, true, false, false

% | T3: false, false, false, false, false, false

% | T4: false, false, false, false, true, false

% | T5: false, false, false, false, false, false

% |];

%----------

% if we're not in ssa, maybe

% array[temp_t, id] of var reg_t;

% since register can change as reuse site.

% Registers don't allocate to same spot

%constraint forall (id in operation_t)(

% forall(t1 in temp_t)(

% forall(t2 in temp_t)(

% (live_in[t1,id] /\ live_in[t2,id] /\ t1 != t2) ->

% reg[t1] != reg[t2]

% )));

Answer Set Programming

Answer set programming has a decent pitch in my opinion to being a natural fit to this problem. One of the supposed utilities of datalog is that it is good for expressing fixed point program analyses. These fixed points are needed to handle loops in the control flow graphs. Answer set programming is a superset of datalog, so it too can express these analyses.

What it adds on top of datalog is a SAT-like solver. Because of this, I would claim that you can naturally express program anlayses in the datalog style, and then make combinatorial choices for register allocation, instruction selection, and instruction scheduling.

I showed how to use datalog for graph matching of instructions here https://www.philipzucker.com/imatch-datalog/

- TOAST: Applying Answer Set Programming to Superoptimisation http://www.cs.bath.ac.uk/tom/toast/

- Generating Optimal Code Using Answer Set Programming 2009

- Superoptimisation: Provably Optimal Code Generation using Answer Set Programmin - crick thesis

Having said all that, Greenberg was highly skeptical of this suggestion.

There are bits and pieces of this below. Perhaps I’ll clean up and comment more on this another day.

Bits and Bobbles

I have been chewing on this stuff for years, and have written more half baked stuff than I care to read.

People are struggling with getting loopy multi block egraph compilers to work. I think integrating single block egraph solves with these techniques is fascinating axis to declaratively combine almost every piece of a backend. It’s relatively straightforward seeming and does not require new insight to do. A single block can be seen as a purely functional expression and can have optimizing rewrites applied in a straightforward manner.

Eli has mentioned that the “-O4” market is underserved. A compiler that ekes out a bit more performance at the cost of huge compile times could save big companies deplaying the same program to a bunch of servers a ton of money.

Fancy egraph extraction is very similar to the declarative instruction selection problem. See Complete and Practical Universal Instruction Selection.

One of my big regrets on the VIBES project was not writing up a checkpoint on the ideas and state of the constraint compiler aspect of it when it was all fresh in my mind and exciting. I

https://discuss.systems/@pkhuong/112118653338441212 Paul Khuong mentions an interesting idea using tree decomposition + dynamic programming for optimal search over the space

Nevertheless, it is quite a cool approach and even in it’s imperfect state it is interesting

iterated register coalescing - appell and george

An interesting perspective is staged metaprogramming. code -> (constraints * (model -> asm))

destination driven is very clean and useful. It is also uses tge backwards processing liveness trick as i recall.

- https://bernsteinbear.com/blog/ddcg/

- https://github.com/tekknolagi/pyddcg

- https://github.com/tekknolagi/ddcg

- https://legacy.cs.indiana.edu/~dyb/pubs/ddcg.pdf

It is a fairly mathemtical and precise problem and also practical feeling. It’s quite fun.

I like constraint solvers. I like them because it’s kind of fun to figure out how to mold your problem into the form they need.

It isn’t all roses. Sometimes using an off the shelf solver requires mangling your problem.

They can be slower than a bespoke heuristics.

In compilation, there are multiple IRs to speak of.

There’s usually some kind of SSA IR like LLVM IR. Then there may be instructions filled in but logical variables instead of registers. And what is given to the assembler isn’t fully concretized. You still have abstract labels for memory addresses and program addresses. Even after you run that, linking or dynamic linking can still occur, so there are relocations describing the ways to fix up the binary.

It’s nice to traverse a block backwards. This is because you can perform a livness analysis at the same time you are making your constraints.

One can push different pieces into the metalevel (python) or the object languages (z3). You can push the liveness ana;lysis into the solver, or the instruction selection, or the assembler.

It all gets more complicated.

The more powerful compile time techniqyes seem to deliver fairly maginal gains. One problem is that the model of cpu operation isn’t that clear. There’s a lot of internal complexity to the CPU (caches, pipelining, out of order execution). Considering these gives rules of thumb.

More straightforward objectives are things like code size. Smaller is always better (well, unless you also care about performance. It is conceivable larger code performs better.).

It is conceivable to have crazier constraints. Like maybe you’re writing shellcode that can’t have certain bytes in it.

Register allocation is often modelled as a graph coloring. This isn’t quite true because it can be the case that if you can get your resgiters right, your peephole optimizer can reduce your code a little bit. The canonical example is a mov x,y instruction. If you can select registers such that x=y, then

Instruction scheduling is the problem of reshuffling your instructions according to your dependencies. It is good to get your memory accesses as early as possible. They are often going to be slower than more computational register to register functions. It’s kind of like firing off an async request.

Memory models

Instruction Selection is a combination of problems. Perhaps it is the richest. Here are some declarative specs of instruction selectors. Go, cranelift. Instruction selection finds patterns. The source can be modelled as Trees, DAGs, or Graphs. See https://www.amazon.com/Instruction-Selection-Principles-Methods-Applications/dp/3319816586

Then it selects a sufficient set of these patterns to actually cover the required function.

Unison

A major touchpoint for compiling with constraints is the Unison compiler.

Unison is an alternative LLVM backend that solves the register allocation problem and instruction selection problem in “unison” using a constraint solving backend.

Unison supported multiple architectures, but one, Hexagon was a very long instruction word (VLIW) architecture. My 10cent discussion of VLIW is that the instruction set allows explicit specification of parallelism / data dependencies. This enables perhaps a more direct model of the actual parallel interworkings of the cpu at the cost of significant compiler complexity. It is here that perhaps constraint compilation carries its weight.

This paper is particular is useful [Combinatorial Register Allocation and Instruction Scheduling])https://arxiv.org/abs/1804.02452). Also very interesting was the manual.

LLVM has multiple IRs. One of them is Machine IR (MIR), which is an IR that has more of the information filled in. Unison takes this output, fiddles with it, and then performs solving. This reuses the frontend, middle end passes, and instruction selection of llvm, which is huge.

The actual unison minizinc model is here. I spent a good month probably studying this and trying to pare this down. Ultimately, I decided to write it from scratch again, adding in pieces as we understood we needed them.

This is an example of a unison IR taken from the manual:

function: factorial

b0 (entry, freq: 4):

o0: [t0:r0,t1:r31] <- (in) []

o1: [t2] <- A2_tfrsi [1]

o2: [t3] <- C2_cmpgti [t0,0]

o3: [] <- J2_jumpf [t3,b2]

o4: [] <- (out) [t0,t1,t2]

b1 (freq: 85):

o5: [t4,t5,t6] <- (in) []

o6: [t7] <- A2_addi [t5,-1]

o7: [t8] <- M2_mpyi [t5,t4]

o8: [t9] <- C2_cmpgti [t5,1]

o9: [] <- J2_jumpt [t9,b1]

o10: [] <- (out) [t6,t7,t8]

b2 (exit, return, freq: 4):

o11: [t10,t11] <- (in) []

o12: [] <- JMPret [t11]

o13: [] <- (out) [t10:r0]

adjacent:

t0 -> t5, t1 -> t6, t1 -> t11, t2 -> t4, t2 -> t10, t6 -> t6, t6 -> t11,

t7 -> t5, t8 -> t4, t8 -> t10

Answer Set Programming

Compiler problems

TOAST: Applying Answer Set Programming to Superoptimisation http://www.cs.bath.ac.uk/tom/toast/ Generating Optimal Code Using Answer Set Programming 2009 Superoptimisation: Provably Optimal Code Generation using Answer Set Programmin - crick thesis

import clingo

def Var(x):

def Add(e1,e2):

def Set(v, e):

prog(plus(a, b)).

expr(E) :- prog(E).

expr(A) :- expr(plus(A,_)).

expr(B) :- expr(plus(_,B)).

isel(add(plus(A,B),A,B)) :- expr(plus(A,B)).

{cover(E,P)} = 1 :- expr(E).

alloc(R,T)

%#show expr/1.

% re

#script (python)

import clingo

def is_const(x):

print(x)

return x.type == clingo.SymbolType.Function and len(x.arguments) == 0

def mkid(x):

if is_const(x):

return x

return clingo.Function("var", [clingo.Number(hash(x))])

#end.

% flatten

expr(E) :- prog(E).

expr(A) :- expr(plus(A,_)).

expr(B) :- expr(plus(_,B)).

% generate possible instruction outputs via pattern matching

%insn(add(V, A1, B1)) :- expr(E), E = plus(A,B), V = @mkid(E), A1 = @mkid(A), B1 = @mkid(B).

pre_insn(add(E, A, B)) :- expr(E), E = plus(A,B).

pre_insn(mov(E,A)) :- expr(E), E = plus(A,0).

pre_insn(mov(E,B)) :- expr(E), E = plus(0,B).

% do the id conversion all at once.

insn(add(E1,A1,B1)) :- pre_insn(add(E,A,B)), E1 = @mkid(E), A1 = @mkid(A), B1 = @mkid(B).

insn(mov(E1,A1)) :- pre_insn(mov(E,A)), E1 = @mkid(E), A1 = @mkid(A).

% Is there really a reason to have separate insn and select?

{select(I)} :- insn(I).

defines(I,V) :- insn(I), I = add(V, A1, B1).

defines(I,V) :- insn(I), I = mov(V, A).

uses(I,A) :- insn(I), I = add(V, A, B).

uses(I,B) :- insn(I), I = add(V, A, B).

uses(I,A) :- insn(I), I = mov(V, A).

% top level output is needed.

used(P1) :- prog(P), P1 = @mkid(P).

{select(I) : defines(I,V)} = 1 :- used(V). % if used, need to select something that defines it.

% if selected, things instruction uses are used. Again if selected

used(A) :- select(I), uses(I,A).

%//{select(A) :- select(add(V,A,B)).

%select

%prog(plus(a, plus(b,c))).

prog(plus(a, plus(plus(0,b),c))).

defines(a,a; b,b; c,c).

%#show expr/1.

#show select/1.

% if used, must be assigned register

{assign(V, reg(0..9)) } = 1 :- used(V).

le(X,Z) :- le(X,Y), le(Y,Z). % transitive

:- le(X,Y), le(Y,X), X != Y. % antisymmettric

le(X,X) :- le(X,_). % reflexive

le(Y,Y) :- le(_,Y).

% instructions must be ordered

{le(I,J)} :- select(I), select(J).

% definitions must become before uses.

le(I,J) :- defines(I,A), used(J,A).

% var is live at instructin I if I comes after definition J, but before a use K.

% using instruction as program point is slight and therefore perhaps alarming conflation

live(I, X) :- defines(J, X), le(J, I), J!=I, le(I,K), uses(K,X).

#show assign/2.

add(0, z, x, y).

add(1, z, x, y).

add(2, )

insn(, add).

insn(, sub, ).

insn(N, mov, ).

:- insn(N), insn(M), N != M. % unique times

:-

:- assign(Temp,R), assign(Temp2,R), live(Temp,T), live(Temp2,T) ; no register clashes.

%#program myprog.

insn(x, add, y , z).

insn(w, mul, x, y).

% identify instruction with the temp it defines. Good or bad?

%#program base.

temp(T) :- insn(T,_,_,_).

temp(T) :- insn(_,_,T,_).

temp(T) :- insn(_,_,_,T).

% scheduling

{lt(U,T); lt(T,U)} = 1 :- temp(T), temp(U), T < U.

lt(T,U) :- lt(T,V), lt(V,U). %transitive

% not lt(T,T). % irreflexive redundant

% :- lt(T,U), lt(U,T). % antisymmettric redundant

% uses

use(T,A) :- insn(T, _, A, _).

use(T,B) :- insn(T, _, _, B).

lt(A,T) :- use(T,A).

% live if U is defined before T and there is a use after T.

live(T,U) :- lt(U,T), lt(T,V), use(V,U).

reg(r(0..9)).

{assign(T,R): reg(R)} = 1 :- temp(T).

:- assign(T,R), assign(U,R), live(U,T).

% minimize number of registers used

#minimize { 1,R : assign(T,R)}.

% try to use lower registers as secondary objective

#minimize { 1,R : assign(T,R)}.

% sanity vs constraints. I expect none of these to be true.

binop(Op) :- insn(_, Op, _, _).

error("assign field is not register", R) :- assign(_,R), not reg(R).

error("assign field is not temp", T) :- assign(T,_), not temp(T).

#script (python)

import clingo

def is_const(x):

return isinstance(x, clingo.Symbol) and len(x.arguments) == 0

def mkid(x):

if is_const(x):

return x

return clingo.Function("v" + str(hash(x)), [])

#end.

prog(plus(a,plus(b,c))).

expr(E) :- prog(E).

expr(A) :- expr(plus(A,_)).

expr(B) :- expr(plus(_,B)).

% It's almost silly, but also not.

insn(@mkid(E), add, @mkid(A), @mkid(B)) :- expr(E), E = plus(A,B).

id(@mkid(E),E) :- expr(E).

#script(python)

import clingo

def my_add(a,b):

return clingo.Number(a.number + b.number)

#end.

test_fact(@my_add(1,2)).

biz.

{foo; bar} = 2 :- biz.

Could use python parser to create code. That’s kind of intriguing.

Free floating and assign to blocks? The graph like structure is nice for sea of nodes perhaps. clingo-dl might be nice for scheduling constraints.

Using clingraph would be cool here.

prog(E).

expr(E) :- prog(E).

% block(B,X,E) % variable X should have expression E in it. This summarizes the block.

% demand. ( dead code elimination kind of actually. )

expr(A;B) :- expr(add(A,B)).

reg(rax;rdi;rsi;r10;r11).

insn(E, x86add(I1,I2)) :- expr(add(A,B)), insn(A,I1), insn(B,I2).

{ insn(E, x86add(R1,R2)) } :- expr(E), E = add(A,B), insn(A,I1), insn(B,I2), reg(R1), reg(R2).

% how to factor representing intructions

{ insn(E, x86add) } :- expr(add(A,B)).

% really its a pattern identifier.

sched(E,I,N) :- insn(E,I), ninsn(N), 0...N.

{ dst(E,x86add,0,R) } :- reg(R), not live(R).

src(E,I,R) :- insn(add(A,B, x86add), dst(A,_,R), dst(B,_,R).

% must schedule value needed before computation

:- sched(add(A,B), I, N), sched(A,I1,M), M >= N.

:- sched(add(A,B), I, N), sched(B,I1,M), M >= N.

% We could schedule at multiple times. That's rematerialization.

% copy packing?

{insn(E, cp)} :- expr(E).

read(src) :- insn(x86add(Dst, Src)).

clobber(Dst;zf;cf) :- insn(x86add(Dst, Src)).

% initial values / calling conventions

value(rdi,x0,0; rsi,x1,0; rcx,x2,0).

value(rax, E, N) :- prog(E), ninsn(N).

live(R,N-1) :- live(R,N), not clobber(R,I,N).

live(R,N-1) :- read(R,N).

ninsn(N) :- N = #count { I : active(E,I) }.

#script (python)

import clingo

def to_asm(t):

if t.name == "add":

return clingo.String("todo")

#end.

prog(E).

expr(E) :- prog(E).

expr(A;B) :- expr(add(A,B)).

child(E,A; E,B):- expr(E), E = add(A,B).

reg(rax;rdi;rsi;r10;r11).

ecount(N) :- N = #count { E : expr(E) }.

{ where(R,E) } = 1 :- reg(R), expr(E).

{ when(1..N,E) } = 1 :- ecount(N), expr(E).

% subexpressions must come earlier

:- when(I, E), when(I2, C), child(E,C), I2 > I.

% time is unique

:- when(I,E1), when(I,E2), E1 != E.

% There can't exist a clobber E1 that occurs

:- child(E,C), where(R,C), where(R, E1), E1 != C,

when(T,E), when(Tc,C), when(T1,E1), Tc < T1, T1 < T.

write(R,T) :- when(T,E), where(R,E).

read(R,T) :- when(T,E), child(E,C), where(R,C).

liver(R,T) :- read(R,T).

liver(R,T-1) :- liver(R,T), not write(R,T).

live(T, C) :- when(T, E), child(E,C).

live(T-1, E) :- live(T,E), not when(T,E), T >= 0.

avail(T,E) :- when(T,E).

avail(T+1,E) :- avail(T,E), where(R,E), not write(R,T), T <= End.

% where = assign ? alloc ?

#minimize { 10, : where(R,E), reg(R) } + { 50, : where(R,E), stack(R) }.

Egraph extraction / Union Find

https://www.philipzucker.com/asp-for-egraph-extraction/

%re

eq(Y,X) :- eq(X,Y).

eq(X,Z) :- eq(X,Y), eq(Y,Z).

term(X) :- eq(X,_).

term(X;Y) :- term(add(X,Y)).

eq(add(X,Y), add(Y,X)) :- term(add(X,Y)).

eq(add(X,add(Y,Z)), add(add(X,Y),Z)) :- term(add(X,add(Y,Z))).

eq(add(X,add(Y,Z)), add(add(X,Y),Z)) :- term(add(add(X,Y),Z)).

term(add(1,add(2,add(3,4)))).

%re

#script(python)

uf = {}

def find(x):

while x in uf:

x = uf[x]

return x

def union(x,y):

x = find(x)

y = find(y)

if x != y:

uf[x] = y

return y

#end.

% :- term(add(X,Y)), rw(X,X1), rw(Y,Y1),

% add( @find(Y) , @find(X) ,@find(XY) ):- add(X,Y,XY).

%rw(T, @union(T,add(@find(X), @find(Y)))) :- term(T), T = add(X,Y). % congruence?

%rw(T, @union(T,add(@find(Y), @find(X)))) :- term(T), T = add(X,Y). % commutativity.

%rw(T, @find(T)) :- term(T).

%rw(X, @find(X); Y, @find(Y)) :- term(add(X,Y)).

%term(T) :- rw(_,T).

term(@union(T, add(@find(X), @find(Y)))) :- term(T), T = add(X,Y).

term(@union(T, add(@find(Y), @find(X)))) :- term(T), T = add(X,Y).

term(@find(X); @find(Y)) :- term(add(X,Y)).

bterm(1,0).

bterm(N+1, add(N,X)):- bterm(N,X), N < 5.

term(X) :- bterm(5,X).

%term(add(1,2)).

#show term/1.

Explicit strata control. Does this work? Does it semi-naive? But I want to add strata for term producing rules

#script(python)

def main(ctl):

for i in range(10):

ctl.ground(["cong", [])]) # aka rebuild

ctl.ground(["rewrite",[])])

ctl.solve()

#prog(rebuild)

add(@find(X),@find(Y),@find(Z)) :- add(X,Y,Z).

add(X,Y,@union(Z,Z1)) :- add(X,Y,Z), add(X,Y,Z1), Z != Z1.

#end.

#prog(rewrite)

add(Y,X,Z) :- add(X,Y,Z).

add()

@end.

#end.

%re

#script(python)

uf = {}

def find(x):

while x in uf:

x = uf[x]

return x

def union(x,y):

x = find(x)

y = find(y)

if x != y:

uf[x] = y

#print(uf)

return y

#end.

add(X,Y,XY) :- term(XY), XY = add(X,Y).

term(X;Y) :- term(add(X,Y)).

term(add(add(add(add(1,2),3),4),5)).

add(@find(Y),@find(X),@find(Z)) :- add(X,Y,Z).

add(@find(X),@find(YZ),@find(XYZ);@find(Y),@find(Z),@find(YZ)) :- add(X,Y,XY), add(XY,Z,XYZ), YZ = @find(add(Y,Z)).

add(@find(X),@find(Y),@find(Z)) :- add(X,Y,Z).

add(@find(X),@find(Y),@union(Z,Z1)) :- add(X,Y,Z), add(X,Y,Z1), Z != Z1.

enode(N) :- N = #count { X,Y,XY : add(X,Y,XY) }.

enode2(N) :- N = #count { X,Y,XY : fadd(X,Y,XY) }.

fadd(@find(X),@find(Y),@find(Z)) :- add(X,Y,Z).

#show enode/1.

#show enode2/1.

Instruction Selection

Complete and Practical Universal Instruction Selection

prog((

set(p2,plus(p1,4)),

set((st,q1), p2),

set(q2, plus(q1,4)),

set((st,p1), q2)

)).

plus(p1,4,p2).

plus(p1,4,p1).

This is doing dag tiling. Graph matching probably doesn’t look that much different.

% demand

expr(X;Y) :- expr(add(X,Y)).

expr(X;Y) :- expr(mul(X,Y)).

{ sel( add, E) } :- expr(E), E = add(X,Y), sel(P1,X), sel(P2,Y).

{ sel( mul, E) } :- expr(E), E = mul(X,Y), sel(P1,X), sel(P2,Y).

{ sel( fma, E) } :- expr(E), E = add(mul(X,Y),Z), sel(P1,X), sel(P2,Y), sel(P3,Z).

@

offset(0;1;2;4;8;16).

{ sel( load, E) } :- expr(E), E = load(add(Addr,N)), sel(P1,Addr), offset(N).

{ sel(reg, E) } :- expr(E), E = var(X). % we don't _have_ to "use" register if something dumb is using it.

{ sel(nop, E) }:- expr(E), E = add(X,0), sel(P,X).

prog(mul(var(x), var(y))).

expr(E) :- prog(E).

pat(P) :- sel(P,_).

%:- #count { sel(P,E) : expr(E),pat(P) } > 1. % only select at most one pattern

:- #count {sel(P, E) : pat(P), prog(E)} = 0.

%#minimize { 1,X,Y : sel(X,Y) }.

#show expr.

Minizinc

Given that we already had experience using z3 and that smt solvers are not that different from constraint programming systems, why go for minizinc?

- Optimization

-

Useful bits

- text file vs bindings. Speed, flexibility, readability, serialization (cost and boon)

The model

% Follow paper exactly. https://arxiv.org/abs/1804.02452 See Appendix A

% Difference from unison model.mzn: Try not using integers. Try to use better minizinc syntax. Much simplified

include "globals.mzn";

%% ---------------------------------------

%% PARAMETERS

%% ---------------------------------------

% Type definitions

% All are enumerative types

enum reg_t;

enum opcode_t;

enum temp_t;

enum hvar_t;

enum operand_t;

enum operation_t;

enum block_t;

array[operand_t] of operation_t : operand_operation; % map from operand to operations it belongs to

array[temp_t] of operand_t : definer; %map from temporary to operand that defines it

array[temp_t] of set of operand_t : users; %map from temporary to operands that possibly use it

array[temp_t] of block_t : temp_block; % map from temporary to block it lives in

set of operation_t : copy; % is operation a copy operation

array[temp_t] of int : width; % Atom width of temporary. Atoms are subpieces of registers. Maybe 8 bit.

array[operand_t] of set of reg_t : preassign; % preassign operand_t to register.

array[temp_t] of set of temp_t : congruent; % Whether congruent. Congruent operands are actually the same temporary split by linear SSA.

array[operation_t] of set of opcode_t : operation_opcodes; % map from operation to possible instructions that implement it

% register class

% For simd registers, spilling.

array[operand_t, opcode_t] of set of reg_t : class_t;

array[opcode_t] of int: latency; % latency of instruction

array[block_t] of operation_t : block_ins;

array[block_t] of operation_t : block_outs;

array[block_t] of set of operation_t : block_operations;

% map from user friendly names to temporaries derived them via linear ssa.

array[hvar_t] of set of temp_t : hvars_temps;

int: MAXC = 100; % maximum cycle. This should possibily be a parameter read from file.

% todo: resource parameter

% con, dur, cap

% todo: objective function parameters.

% weight

% cost

%% -------------------

%% Solution exclusion

%% ---------------------

int : number_excluded;

set of int : exclusions = 1..number_excluded;

array[exclusions, temp_t] of reg_t : exclude_reg;

/* array[exclusions, operation_t] of opcode_t : exclude_insn;

array[exclusions, operand_t] of temp_t : exclude_temp;

array[exclusions, temp_t] of bool : exclude_live;

array[exclusions, operation_t] of bool : exclude_active;

array[exclusions, operation_t] of 0..MAXC : exclude_issue; % maybe make these ranges. I could see a good argument for that

array[exclusions, temp_t] of 0..MAXC : exclude_start_cycle;

array[exclusions, temp_t] of 0..MAXC : exclude_end_cycle;

*/

%% ---------------------------------------------------------------

%% VARIABLES

%% ---------------------------------------------------------------

array[temp_t] of var reg_t : reg;

array[operation_t] of var opcode_t : opcode;

array[operand_t] of var temp_t : temp;

array[temp_t] of var bool : live;

array[operation_t] of var bool : active;

array[operation_t] of var 0..MAXC : issue; % maybe make these ranges. I could see a good argument for that

array[temp_t] of var 0..MAXC : start_cycle;

array[temp_t] of var 0..MAXC : end_cycle;

%% ------------------------------

%% CONSTRAINTS

%% ------------------------------

% Exclude all previous solutions

constraint forall(n in exclusions)(

exists( t in temp_t )( reg[t] != exclude_reg[n,t] )

%\/ exists( o in operation_t )( opcode[o] != exclude_opcode[n,o] )

%\/ exists( o in operand_t )( temp[o] != exclude_temp[n,o] )

%\/ exists( t in temp_t )( live[t] != exclude_live[n,t] )

%\/ exists( o in operation_t )( active[o] != exclude_active[n,o] )

%\/ exists( o in operation_t )( issue[o] != exclude_issue[n,o] )

%\/ exists( t in temp_t )( start_cycle[t] != exclude_start_cycle[n,t] )

%\/ exists( t in temp_t )( end_cycle[t] != exclude_end_cycle[n,t] )

);

% function nonempty?

% constraint to choose instruction from allowed instructions. Why was this not implied

% not in the paper

% maybe if I had more logic interconnecting choice of temporary / register with opcode this would be implied

constraint forall(o in operation_t where card(operation_opcodes[o]) > 0 )(

opcode[o] in operation_opcodes[o]

);

% operand should only be assigned to temporary it either defines or uses.

% Is this implicit from other constraints?

constraint forall(o in operand_t)(

temp[o] in { t | t in temp_t where definer[t] = o \/ o in users[t] }

);

/*

constraint forall(t in temp_t)(

temp[definer[t]] = t

);

constraint forall(t in temp_t)(

forall(o in operand_t)(

exists() temp[o] = t

)

temp[users[t]] = t

);

*/

%C1.1

% no overlap constraint for live register usage

% use cumulative?

% use minizinc built-in diffn.

% The original unison model uses many different options

function array[int] of var int : block_array(array[temp_t] of var int : a, block_t : b) =

[a[t] | t in temp_t where temp_block[t] = b ];

% [diffn_nonstrict] https://www.minizinc.org/doc-latest/en/lib-globals.html#packing-constraints

% Constrains rectangles i , given by their origins ( x [ i ], y [ i ]) and

% sizes ( dx [ i ], dy [ i ]), to be non-overlapping. Zero-width rectangles can be packed anywhere.

% still need to include live[t] condition

constraint forall(blk in block_t)(

diffn(block_array(reg,blk), % built in global minizinc constraint

block_array(start_cycle,blk),

% block_array([width[t] * bool2int(live[t]) | t in temp_t ], b), % no this is bad

block_array(width, blk),

[end_cycle[t] - start_cycle[t] | t in temp_t where temp_block[t] = blk])

);

% C2.1 Pre-assignment to registers

constraint forall(p in operand_t) (

forall(r in preassign[p])(

reg[temp[p]] = r

)

);

% C3.2. register class constraint

constraint forall(p in operand_t where active[operand_operation[p]])(

reg[temp[p]] in class_t[p, opcode[operand_operation[p]]]

);

% C4 Every operation that is not a copy must be active.

constraint forall(o in operation_t where not (o in copy))(

active[o]

);

% C5.1 A temporary is live if its defining operation is active

constraint forall(t in temp_t)(

live[t] = active[operand_operation[definer[t]]]

);

% C5.2 For an active operation there must be at least one live temporary available

constraint forall(t in temp_t)(

%card({p | p in users[t] where live[t] == active[operand_operation[p]] /\ temp[p] == t}) >= 1 % fishy encoding

live[t] <- exists(p in users[t])( active[operand_operation[p]] /\ temp[p] = t ) % should be both way implication?

);

% C6 Congruent temps map to the same register

constraint forall (p in temp_t, q in temp_t where q in congruent[p])(

reg[p] = reg[q]

);

%% Instruction Scheduling Constraints

% C7.1 The issue cycle of operations that define temporaries must be before all

% active operations that use that temporary

constraint forall (t in temp_t)(

let {operand_t : p = definer[t]} in

forall(q in users[t] where active[operand_operation[q]] /\ temp[q] == t)(

issue[operand_operation[q]] >= issue[operand_operation[p]] + latency[opcode[operand_operation[p]]]

)

);

% resource consumptions contraint

% TODO. We are not tracking resource consumption yet

/*

use cumulative

constraint forall (b in block_ts)(

forall (s in Resource)

)

*/

%% Integration Constraints

% C9 The start cycle of a temporary is the issue cycle of it's defining operation

constraint forall (t in temp_t where live[t])(

start_cycle[t] == issue[operand_operation[definer[t]]]

);

% Not in paper. Do we want this?

% end is at least past the start cycle plus the latency of the operation

/*

constraint forall (t in temp_t)(

end[t] >= start[t] + latency[ opcode[ operand_operation[definer[t]] ]]

);

*/

%C10 Then end cycle of a temporary is the last issue cycle of operations that use it.

constraint forall (t in temp_t where card(users[t]) > 0 /\ live[t])(

end_cycle[t] == max(

% [ start[t] + 10 ] ++ % a kludge to make minizinc not upset when users[t] is empty.

[ issue[operand_operation[p]] | p in users[t] where temp[p] == t ] )

% shouldn't this also be contingent on whether the user is active?

% I suppose the temporary won't be live then.

);

% In blocks must be at start of block

% Outs must be at end

constraint forall (blk in block_t)(

issue[block_ins[blk]] == 0

/\

% worse but possibly faster

% issue[block_outs[blk]] == MAXC

forall(o in block_operations[blk]) (issue[o] <= issue[block_outs[blk]])

);

% anything that has a where clause that isn't just parameters makes me queasy. What is this going to do?

%----------------------

% HELPERS

%----------------------

predicate set_reg(hvar_t: hvar, reg_t: r) =

forall(t in hvars_temps[hvar])(reg[t] = r);

predicate exclude_reg(reg_t: r) =

forall(t in temp)(reg[t] != r);

%--------------------------------

% OBJECTIVE

%-------------------------------

% Minimize number of registers

solve minimize card( {r | p in operand_t, r in reg_t where reg[temp[p]] = r } );

%TODO. For the moment, mere satisfaction would make me happy

% minimize max( [end[t] | t in temp_t ] ) % total estimated time (spilling is slow)

% minimize resource usage

% solve minimize max( end );

% solve minimize max( reg ); % use smallest number of registers

Shallow Minizinc DSL

arch spcific. Arm

enum reg = {R0, R1, R2,

Stack0, Stack1, Stack2,

Mem,

ZF,

CF};

%enum pseudo_temp

callee_saved =

caller_saved =

gpr = {R0, R1, R2};

stack

predicate gpr(temp_t : t) =

reg[t] in {R0, R1, R2};

predicate mov(temp_t t1, temp_t t2) =

insn([t1], "mov", [t2]) /\ gpr(t1) /\ gpr(t2);

predicate binop(temp_t t1, temp_t t2, temp_t t3) =

insn([t1], "mov", [t2]) /\ gpr(t1) /\ gpr(t2) /\ gpr(t3);

% style not good for programmatic discovered insns

% could pretty print it.

predicate arm(id, lhs, opcode, rhs) =

if opcode = "mov" then

insn() /\ gpr() /\ gpr()

elseif opcode = "add" \/ opcode = "mul" \/ then

isns(opcode)

elseif

endif

model 3

% Follow paper exactly. https://arxiv.org/abs/1804.02452 See Appendix A

% Difference from unison model.mzn: Try not using integers. Try to use better minizinc syntax. Much simplified

include "globals.mzn";

% Type definitions

% All are enumerative types

enum reg_t = {R0,R1,R2, R3, R4};

enum block_t;

enum temp_t;

int: MAXC = 100; % maximum cycle. This should possibily be a parameter read from file.

predicate insn_c(operation_t : id, list of temp_t : lhs, string : opcode, list of temp_t : rhs) =

all_equal([start_cycle[t] | t in lhs]) /\

forall(t in lhs)(

live[t] /\ % definer active

issue[id] + 1 = start_cycle[t] /\

end_cycle[t] >= issue[id] + 1)

/\

forall(t2 in rhs)(

live[t2] /\ %user active

issue[id] >= start_cycle[t2] /\ % t2 is already defined

end_cycle[t2] >= issue[id] % t2 ends

);

predicate insn(operation_t : id, list of temp_t : lhs, string : opcode, list of temp_t : rhs) =

active[id] /\ insn_c(id,lhs,opcode,rhs);

predicate insn_opt(operation_t : id, list of temp_t : lhs, string : opcode, list of temp_t : rhs) =

active[id] -> insn_c(id,lhs,opcode,rhs);

% still need to include live[t] condition

constraint diffn(reg, % built in global minizinc constraint

start_cycle,

% block_array([width[t] * bool2int(live[t]) | t in temp_t ], b), % no this is bad

[1 | t in temp_t],

[end_cycle[t] - start_cycle[t] | t in temp_t]);

array[temp_t] of var reg_t : reg;

array[temp_t] of var 0..MAXC : start_cycle; % def_cycle

array[temp_t] of var 0..MAXC : end_cycle; % death_cycle

array[operation_t] of var bool : active;

array[operation_t] of var 0..MAXC : issue;

array[temp_t] of var bool : live;

% https://www.minizinc.org/doc-2.5.5/en/sat.html

% useful for alternative instructions.

predicate atmostone(array[int] of var bool:x) =

forall(i,j in index_set(x) where i < j)(

(not x[i] \/ not x[j]));

predicate exactlyone(array[int] of var bool:x) =

atmostone(x) /\ exists(x);

predicate alt_insn(list of operation_t : ops) =

exactlyone([active[o] |o in ops]);

predicate preassign(temp_t : t, reg_t : r) = reg[t] = r;

predicate cong(temp_t : t1, temp_t : t2) =

reg[t1] = reg[t2] /\ live[t1] = live[t2];

predicate outs(list of temp_t : ts) =

forall( t in ts)(end_cycle[t] = MAXC);

predicate ins(list of temp_t : ts) =

forall( t in ts)(start_cycle[t] = 0);

predicate force_order(operation_t : id1, operation_t : id2) =

issue[id1] < issue[id2];

% Program specific data:

/*

enum block_t = {B1};

enum temp_t = {T1,T2,T3};

set of int : operation_t = 1..3;

constraint preassign(F,R0);

constraint

ins([T3]) /\

insn(1, [T1], "add", [T2,T3]) /\

insn(2, [T2], "mov", [T3]) /\

outs([T1]);

*/

block_t = {Begin, Loop, End};

temp_t = {FB,NB, FL1, FL2, NL1, NL2, };

set of int : operation_t = 1..3;

constraint preassign(NB,R0);

constraint

ins([NB]) /\

insn(1, [FB], "mov", []) /\ % mov F, 1

outs([NB,FB]) /\

ins([NL1,FL1]) /\

insn(2, [FL2], "mul", [FL1, NL1] ) /\

% insn(3, [NL2], "dec", [NL1]) /\ cong(NL1,NL2) /\

% jmp loop if NL2 > 0

outs([NL2, FL2]) /\

% ret

cong(FB,FL1) /\

cong(NB, NL1) /\

cong(NL1,NL2);

no reorder

% Follow paper exactly. https://arxiv.org/abs/1804.02452 See Appendix A

% Difference from unison model.mzn: Try not using integers. Try to use better minizinc syntax. Much simplified

include "globals.mzn";

% Type definitions

% All are enumerative types

enum reg_t = {R0,R1,R2};

enum block_t = {B1};

enum temp_t = {T1,T2,T3};

int: MAXC = 100; % maximum cycle. This should possibily be a parameter read from file.

predicate insn(int : id, list of temp_t : lhs, string : opcode, list of temp_t : rhs) =

forall(t in lhs)(

start_cycle[t] = id /\

forall(t2 in rhs)(

start_cycle[t] > start_cycle[t2] /\ % t2 is already started

end_cycle[t2] >= start_cycle[t] %

)

);

% still need to include live[t] condition

constraint diffn(reg, % built in global minizinc constraint

start_cycle,

% block_array([width[t] * bool2int(live[t]) | t in temp_t ], b), % no this is bad

[1 | t in temp_t],

[end_cycle[t] - start_cycle[t] | t in temp_t]);

array[temp_t] of var reg_t : reg;

array[temp_t] of var 0..MAXC : issue; % def_cycle

array[temp_t] of var 0..MAXC : start_cycle; % def_cycle

array[temp_t] of var 0..MAXC : end_cycle; % death_cycle

predicate preassign(temp_t : t, reg_t : r) = reg[t] = r;

predicate outs(list of temp_t : ts) =

forall( t in ts)(end_cycle[t] = MAXC);

predicate ins(list of temp_t : ts) =

forall( t in ts)(start_cycle[t] = 0);

% Program specific data:

constraint preassign(T1,R2);

constraint

ins([T3]) /\

insn(1,[T2], "mov", [T3]) /\

insn(2,[T1], "add", [T2,T3]) /\

outs([T1]);

basic

% Follow paper exactly. https://arxiv.org/abs/1804.02452 See Appendix A

% Difference from unison model.mzn: Try not using integers. Try to use better minizinc syntax. Much simplified

include "globals.mzn";

% Type definitions

% All are enumerative types

enum reg_t = {R0,R1,R2};

enum block_t = {B1};

enum temp_t = {T1,T2,T3};

int: MAXC = 100; % maximum cycle. This should possibily be a parameter read from file.

predicate insn(list of temp_t : lhs, string : opcode, list of temp_t : rhs) =

all_equal([start_cycle[t] | t in lhs]) /\

forall(t in lhs)(

forall(t2 in rhs)(

start_cycle[t] > start_cycle[t2] /\ % t2 is already started

end_cycle[t2] >= start_cycle[t] %

)

);

% still need to include live[t] condition

constraint diffn(reg, % built in global minizinc constraint

start_cycle,

% block_array([width[t] * bool2int(live[t]) | t in temp_t ], b), % no this is bad

[1 | t in temp_t],

[end_cycle[t] - start_cycle[t] | t in temp_t]);

array[temp_t] of var reg_t : reg;

array[temp_t] of var 0..MAXC : start_cycle; % def_cycle

array[temp_t] of var 0..MAXC : end_cycle; % death_cycle

predicate preassign(temp_t : t, reg_t : r) = reg[t] = r;

predicate outs(list of temp_t : ts) =

forall( t in ts)(end_cycle[t] = MAXC);

predicate ins(list of temp_t : ts) =

forall( t in ts)(start_cycle[t] = 0);

% Program specific data:

constraint preassign(T1,R2);

constraint

ins([T3]) /\

insn([T1], "add", [T2,T3]) /\

insn([T2], "mov", [T3]) /\

outs([T1]);

bool live

enum reg_t = {R0, R1, R2, R3};

enum temp_t = {T0, T1, T2, T3, T4, T5};

int : MAXID = 5;

set of int : operation_t = 0..MAXID;

array[temp_t, operation_t] of var bool : live_in;

array[temp_t] of var reg_t : reg;

predicate insn(operation_t : id, list of temp_t : lhs, string : opcode, list of temp_t : rhs) =

% https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Live_variable_analysis

forall(t in temp_t)(

if (t in rhs) % in gen set

then live_in[t, id] = true

elseif (t in lhs) % not in gen set, in kill set

then live_in[t,id] = false

else % propagate

live_in[t,id] <- live_in[t, id + 1]

endif) /\

% Assignments need to go to different registers than live variables of next instruction.

forall(t1 in lhs)(

forall(t2 in temp_t where t1 != t2)(

live_in[t2,id+1] -> reg[t1] != reg[t2]

));

% Nothing is live at end of block

constraint forall(t in temp_t)( live_in[t, MAXID] = false);

constraint

insn(0, [T1], "mov", [T0]) /\

insn(1, [T2], "add", [T0, T1]) /\

insn(2, [T3], "sub", [T0, T1]) /\

insn(3, [T4], "mul", [T1, T2]) /\

insn(4, [T5], "inc", [T4]);

%reg = [T0: R2, T1: R0, T2: R1, T3: R2, T4: R0, T5: R0];

%live_in =

%[| 0: 1: 2: 3: 4: 5:

% | T0: true, true, true, false, false, false

% | T1: false, true, true, true, false, false

% | T2: false, false, true, true, false, false

% | T3: false, false, false, false, false, false

% | T4: false, false, false, false, true, false

% | T5: false, false, false, false, false, false

% |];

%----------

% if we're not in ssa, maybe

% array[temp_t, id] of var reg_t;

% since register can change as reuse site.

% Registers don't allocate to same spot

%constraint forall (id in operation_t)(

% forall(t1 in temp_t)(

% forall(t2 in temp_t)(

% (live_in[t1,id] /\ live_in[t2,id] /\ t1 != t2) ->

% reg[t1] != reg[t2]

% )));

Was it worth it?

Ideas on improvements

Declarative Code Gen

- Relational Processing for Fun and Diversity minikanren

- Denali - a goal directed super optimizer egraph based optimization of assembly

- PEG egraph cfg

- RVSDG

- minimips minikanren mips assembler/disassembler

-

Parsing and compiling using Prolog There is also a chapter in the art of prolog

- https://www.cs.tufts.edu/~nr/pubs/zipcfg.pdf zgraph

- hoopl https://hackage.haskell.org/package/hoopl-3.7.7.0/src/hoopl.pdf a framework for transformations

Unison

diversification make many versions of binary to make code reuse attacks harder. disunison

Toy Program:

If you do liveness analysis ahead of time, it really does become graph coloring, with an edge between every temporary that is live at the same time.

You cannot do liveness ahead of time if you integrate instruction scheduling with allocation. It needs to be internalized.

If you do SSA ahead of time, you have more flexibility to change colors/register at overwrite points

How to communicate to minizinc:

- Serialized files or C bindings

- Parameters or constraints. In some sense, you a writing a constraint interpreter over the parameters. Why not cut out the middleman? 1: less clear what the structure is. 2. It forces your hand with the bundling of different pieces. Many things need to be bundled into the

insnpredicate unless you reify theinsnpredicate to a variable, in which case you are rebuilding the parameter version.

There is a spectrum of more or less complex models you can use.

Fixed Instruction Order

This makes a DSL in minizinc that looks like a somewhat reasonable IR. It uses a predicate function insn that takes in the lhs and rhs temporaries. It assigns a register to each temporary such that it never clobbers a live variable.

I could do the liveness analysis completely statically, but I choose to internalize it into the model for ease.

enum reg_t = {R0, R1, R2, R3};

enum temp_t = {T0, T1, T2, T3, T4, T5};

int : MAXID = 5;

set of int : operation_t = 0..MAXID;

array[temp_t, operation_t] of var bool : live_in;

array[temp_t] of var reg_t : reg;

predicate insn(operation_t : id, list of temp_t : lhs, string : opcode, list of temp_t : rhs) =

% https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Live_variable_analysis

forall(t in temp_t)(

if (t in rhs) % in gen set

then live_in[t, id] = true

elseif (t in lhs) % not in gen set, in kill set

then live_in[t,id] = false

else % propagate

live_in[t,id] <- live_in[t, id + 1]

endif) /\

% Assignments need to go to different registers than live variables of next instruction.

forall(t1 in lhs)(

forall(t2 in temp_t where t1 != t2)(

live_in[t2,id+1] -> reg[t1] != reg[t2]

));

% Nothing is live at end of block

constraint forall(t in temp_t)( live_in[t, MAXID] = false);

constraint

insn(0, [T1], "mov", [T0]) /\

insn(1, [T2], "add", [T0, T1]) /\

insn(2, [T3], "sub", [T0, T1]) /\

insn(3, [T4], "mul", [T1, T2]) /\

insn(4, [T5], "inc", [T4]);

%reg = [T0: R2, T1: R0, T2: R1, T3: R2, T4: R0, T5: R0];

%live_in =

%[| 0: 1: 2: 3: 4: 5:

% | T0: true, true, true, false, false, false

% | T1: false, true, true, true, false, false

% | T2: false, false, true, true, false, false

% | T3: false, false, false, false, false, false

% | T4: false, false, false, false, true, false

% | T5: false, false, false, false, false, false

% |];

%----------

% if we're not in ssa, maybe

% array[temp_t, id] of var reg_t;

% since register can change as reuse site.

% Registers don't allocate to same spot

%constraint forall (id in operation_t)(

% forall(t1 in temp_t)(

% forall(t2 in temp_t)(

% (live_in[t1,id] /\ live_in[t2,id] /\ t1 != t2) ->

% reg[t1] != reg[t2]

% )));

How do you want to talk about the solution space.

- a next(id1,id2) matrix

- live[id,t] matrix vs start end cycle integers.

% since we don’t record the gen kill sets we need to do this in here.

% next[i,j] where you see id + 1

I was assuming SSA, but maybe it can handle non ssa? Noo. It probably can’t.

Scheduling and Allocation

We can also use a next[i,j] matrix or change live to a start end cycle parameter.

Multiple Blocks

Register Packing

Using the rectangle packing constraint for register modelling

Rewrite Rules

peephole optimization cranelift isle Verifying and Improving Halide’s Term Rewriting System with Program Synthesis

See: e-graphs scheduling using unimodular modelling

Instruction Selection

Automatically Generating Back Ends Using Declarative Machine Descriptions dias ramsey https://www.cs.tufts.edu/~nr/pubs/tiler-abstract.html

Maximal munch parsing http://www.cs.cmu.edu/afs/cs/academic/class/15745-s07/www/lectures/lect9-instruction_selection_745.pdf Like parser generators / libraries, you can make instruction selection libraries / generators. Bottom up vs top down

-

TWIG BURG BEG bottom up generate instruction selectors

iburg https://github.com/drh/iburg a code generator generator

Synthesizing an Instruction Selection Rule Library from Semantic Specifications

Subgraph isomorphism problem VF2 algorithm Very similar to “technology mapping” in the vlsi community.

| type aexpr = Mul | Add |

Macro expansion

- procede bottom up Maximal Munch

Instruction selection is taking a program and figuriing out which instructions can be used to implement this. Typically this leaves behind still some problems to solve, in particular register allocation and instruction scheduling. Presumably, everything in the program needs to be done. We have some notion of correspondence between the program representation and the available instructions. The exact nature of this correspondence depends on how we represent our program.

- Sequence

- Tree - One representation of a program might be as a syntax tree, say

(x + (y * z)). - DAG - consider

(x + y) * (x + y). Really we want to note common shared computation and not recomputex+ ytwice. DAGs and the technique of hash consing can be useful here. - Tree-like DAGS

- CFG - A different representation might be to separate out blocks and control edges between them. Blocks consist of a sequence of statements.

If the statements are purely for assignment, assignment can be inlined. The block is nearly purely functional in some sense. It can be compressed into a functional form like the DAG or Tree by inlining. The block could also itself be considered as a graph, as there is often more then one equivalent way of sequencing the instructions.

The simplest case to consider is that of the tree. We can enumerate patterns in the tree that we know how to implement using instructions. The relationship between tree patterns and instructions can be many-to-many. We should understand how to implement every node in the tree (?a + ?b), (?a * ?b) with a pattern consisting of a sequence of instructions for completeness (ability to compile any tree). We also should try to figure out the tree patterns that correspond to a single assembly instruction like load reg [reg+n] because these will often be efficient and desirable.

There are two distinct and often separable problems here:

- Find pattern matches

- Pick which matches to actually use aka pattern selection

A direct approach to describing patterns is to develop a datatype of patterns. This datatype will be basically the datatype of your AST with holes. This is clearly duplication and becomes painful the more constructors your language has, but whatever.

type ast = Add of ast * ast | Var of string

type ast_pat = Hole of string | PAdd of ast_pat * ast_pat | PVar of string

pmatch : ast_pat -> ast -> (string * ast) list option

Alternatively, we can note that the main point of a pattern is to pattern match and use a church-ish/finalish representation

type ast_pat' = ast -> (string * ast) list option

let convert_pat' : ast_pat -> ast_pat' = pmatch

type var = string

type stmt = Ass of var * expr

type expr = Add of var * var | Var of var

type blk = stmt list

let inline : blk -> (var * ast) list

type insn = Mov of reg * reg | Add of reg * reg | Add2 of reg * reg * reg

A novelty of the Blindell et al work is the notion of universal function (UF) graph. There is both the functinal repsentation of data values, but also cfg is represented as opaque nodes. The correspondence of where values are defined and where computations happen is left up to the constraint solver.

What is the input language? Is it a pure expression langage? A side effectful imperative language? We can convert between these.

I have directly gone to effectful assembly from pure expression language above.

I understand enough to have many questions. What is the input language over which one is pattern matching. Perhaps language is already the wrong word since language tends to imply something tree-like. Is it a pure language or an imperative language. Is it represented as a sequence of IR instructions, a tree, tree-like dag, dag, a graph, or something else. Is represented too weak a word for this question which seems to be very important? “BIL” represented as a sequence vs as a graph might as well be nearly entirely different things. It seems totally possible to translate between pure and imperative, and between the representations and yet it matters so much. What is the output language. It structurally isn’t concrete assembly in many ways. It is definitely un-register allocated and probably unsequenced. Sometimes it feels like tree-like quasi assembly, where the node represents an “output” register even though assembly is really just a sequence of effects. Is there freedom to choose any N^2 combination of structural representations between input and output languages, purity and impurity? None of this even starts to touch control flow. None of this touches what does “overlapping” of patterns mean and what should be allowed

Sequenced representation: Patterns may need to stretch over bits / reorderings. The sequence of the input language does not at all have to be the sequence of the output. Restricting yourself in this way

You can often macro repeat patterns in ways to undo any arbitrary choices made by the representation. Some kind of quotienting. If we have an order free representation, we could aebitrary sequence it, and then sequence the patterns into all possible sequencings. Then you end up with baically the same thing. You can’t go the other way in general. There is something that feels galois connection-y here.

What is the output of pattern matching? Typically I would consider the output of a pattern match to be just pattern variable bindings. But in this case, really we may need full identification between pattern nodes and pattee nodes since this defines the covering.

There are different axes upon which to consider graph variations

- input/output Edges ordered or unordered / have identity are interchangeable. AST tree have identity. Consider the example of a power or any non commutative operation. Edges with identities may want to be considered to be attached to “ports”

- Zero/many input output edges (trees)

- Labels on vertices and or edges

Different kinds can be embedded in each other. Trees can represent graphs if you are allowed to indirectly refer to nodes via labels. Hash cons dags can have many input and output edges. However the output edges of the hash cons are unported, whereas the input edges are ported. The symmettry can be improved by using projection/port nodes connected to the output. In some sense the output of the original is then Operads

You could take a relational perspective on operations, having neither input not output.

Register Allocation

iterated register coalescing - appell and george move edges are considered special because the can be coalesced (collapse the node in the interference graph) nodes with less than number of register nighbors can be removed and you can construct a coloring conservative coalescing - constants can be spilled cheaply via rematerialization

flambda reg alloc points to an appell paper - iterated register coalescing and tiger book https://arxiv.org/abs/1804.02452

cranelift regalloc great blog post

The Solid-State Register Allocator https://www.mattkeeter.com/blog/2022-10-04-ssra/ Belady’s OPT algorithm page faults

The Power of Belady’s Algorithm in Register Allocation for Long Basic Blocks efficient global register allocation

linear scan register allocation

The typical starting point of register allocation is support you’ve been given as assembly program that doesn’t have registers filled in like

# input v1 v2 v3

mov v1, v2

add v1, v1

mul v3, v1

# output v3

The interference graph has an edge between any two variables that are live at the same time. Live means that the variable has been made and someone still needs to use it now or later. In this example, if we assume v1 v2 & v3 are live at the beginning, v1 is live for all 3 instructions, v3 is live for all three and at the output, but v2 is only live at the first instruction since it is never used again.

dsatur graph coliring heurisitc

RL4ReAl: Reinforcement Learning for Register Allocation Compiler gym

Instruction Scheduling

The pure instruction scheduling problem might occur even at the IR level. We can imagine an imperative IR. Certain operations commute and others don’t. We may want to minimize the liveness time of variables for example. This would make sense as a pre-processing step to a sequence input language to an instruction selector.

Instruction scheduling can be parametrized as:

- an embedding into actual time (cycle issue time probably). This is important if you are optimizing for runtime and can get estimates of how long each instruction takes.

- a ranking as integers

- next(i,j) relation which is basically integers. Allows for partial order. after(i,j) :- next(i,k), after(). after is path connected in temporal dag. Possibly this is mappable into a lattice notion of time (i,j,k,etc)?

SuperOptimizers

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Superoptimization

Superoptimizer – A Look at the Smallest Program Massalin https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=25196121 discussion

- Souper https://github.com/google/souper https://arxiv.org/pdf/1711.04422.pdf

- STOKE https://cs.stanford.edu/people/eschkufz/docs/asplos_13.pdf

- TOAST an ASP based one? https://purehost.bath.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/187949093/UnivBath_PhD_2009_T_Crick.pdf

-

GSO gnu superoptimizer

https://twitter.com/kripken/status/1564754007289057280?s=20&t=KWXpxw5bjeXiDnNeX75ogw Zakai binaryen superopitmizer

Compiling with Constraints I

Hey Hey! We’ve open sourced our project VIBES (Verified, Incremental Binary Editing with Synthesis).

A compiler can be a complicated thing. Often we break up and approach the problem by breaking it into pieces. The front end takes text and converts it to a tree. In turn it is often converted to some kind of intermediate representation, say a control flow graph. The middle end performs rearrangements and analyses on this graph. The back end is in charge of taking this intermediate representation and bringing it to executable machine code.

The backend of a compiler has a number of different problems

- Instruction Selection - Take

x := a + band turn it intomov x, a; add x,b - Register Allocation - Take

add x,aand turn it intoadd R0, R1 - Instruction Scheduling - Rearrange instructions to maximize throughput of CPU. Internally cpu has pipelines and resources, store and loads to memory are slow, you want to make sure these are chugging along and interleaved well.

Typically, these will be run one after the other in some order, with greedy-ish algorithms and hand tuned code. This works pretty well and is fast to compile. It does leave performance and size of the resulting code on the table. The Unison approach is trying to build a non toy compiler that uses declarative constraint programming to solve these in concert. Now any optimization is only as good as our modelling of the situation. This is one of the common fallacies of godhood people get when they think about applying math to problems. If your model of the cpu is coarse, then perfectly optimizing with respect to this . Ultimately, every ahead of time model is bad because it must be unable to know information that is readily accessible at runtime. This is at least one reason why without experimentation and measurement, you really can’t tell whether crass online optimization can deliver superior results to thorough ahead of time optimization. See for example JITs, branch prediction, VLIW architectures, out of order execution.

Can I write CFG programs directly in minizinc in a good way? Would avoid 1 indirection or going in and out of a language

Declarative Solving for Compiler Backends using Minizinc Unison-style Compiler backends

Declarative compilation

Combinatorial Register Allocation and Instruction Scheduling

Schulte course on constraint programming https://kth.instructure.com/courses/7669/files/folder/lectures? on compilers https://kth.instructure.com/courses/6414/files

Graph Coloring and Register Allocation

In any case we are embedding a liveness analysis into minizinc. live(t,i) = true/false next(i1,i2) = true/false next forms total order.

[after(i,k) <- next(i,j), after(j,k) for i,j,k in insns] [after(i,k) <-> exists(j in insn)( next(i,j) /\ after(j,k)) \/ next(i,k) forall i,k ] [live[insn, temp] <- ]

Instruction Scheduling

The pure instruction scheduling problem might occur even at the IR level. We can imagine an imperative IR. Certain operations commute and others don’t. We may want to minimize the liveness time of variables for example. This would make sense as a pre-processing step to a sequence input language to an instruction selector.

Instruction scheduling can be parametrized as:

- an embedding into actual time (cycle issue time probably). This is important if you are optimizing for runtime and can get estimates of how long each instruction takes.

- a ranking as integers

- next(i,j) relation which is basically integers. Allows for partial order. after(i,j) :- next(i,k), after(). after is path connected in temporal dag. Possibly this is mappable into a lattice notion of time (i,j,k,etc)?

Instruction matching as an SMT problem

Why is there such an impulse to model these problems in a purely functional style? Invariably we need to introduce a state threading.

Dataflow analysis with Datalog. I should lay out what I understand of the unison compiler.

Register Packing Instruction Scheduling1

The box model

Christian Schulte course

simple

include "alldifferent.mzn";

include "all_equal.mzn";

include "diffn.mzn";

set of int : reg_t = 1..4;

set of int : temp_t = 1..10;

set of int : instr_t = 1..10;

array[temp_t] of var reg_t : reg;

array[temp_t] of var instr_t : def;

array[temp_t] of var instr_t : death;

/*

There is a possible off by one error

is death at the last use site, or is it the instruction after

Let's say it is the last use site.

Or rather should we be thinking of program points between instructions

*/

%constraint alldifferent(def);

predicate insn(array[int] of var temp_t : defs, string: operator, array[int] of var temp_t : uses) =

all_equal([def[t] | t in defs ] )

/*

forall(t2 in defs)(

def[t1] = def[t2]

) */

/\

forall( t1 in defs)(

forall (t2 in uses) (

def[t1] > def[t2] /\ death[t2] >= def[t1]

)

);

% redundant?

constraint forall(t in temp_t)(

def[t] <= death[t]

);

%output ["foo" | t in temp_t];

constraint diffn( reg, def , [1 | t in temp_t], [ death[t] - def[t] | t in temp_t ] );

%constraint diffn( reg, def , reg, [ death[t] - def[t] | t in temp_t ] );

/*

We can't do it this way because alldifferent takes a compile time array.

We could do this if we had a set of dummy values,

Or if we ahead of time fixed the instruction ordering.

If wwe did that, liveness analysis might need to be done out of minizinc.

constraint forall( i in instr_t)(

alldifferent( [ reg[t] | t in temp_t where i < death[t] /\ def[t] < i ] )

); */

constraint insn( [3], "add", [1,2] );

constraint insn( [4], "sub", [1,3] );

solve minimize card(array2set(reg));

ordered

include "alldifferent.mzn";

/*

This file shows register allocation if we prefix the instruction order.

*/

set of int : reg_t = 1..4;

set of int : temp_t = 1..4;

%set of int : instr_t = 1..10;

array[temp_t] of var reg_t : reg;

%array[temp_t] of var instr_t : def;

%array[temp_t] of var instr_t : death;

enum inout = {Out, In};

set of int : instr_t = 1..4;

array[instr_t,inout] of set of temp_t : instrs =

[|

{1,2}, {} |

{3}, {1,2} |

{4}, {2,3} |

{}, {1,4}

|];

array[temp_t] of int : def =

[ min([ i | i in instr_t where t in instrs[i,Out] ]) | t in temp_t ] ;

array[temp_t] of int : death =

[ max([ i | i in instr_t where t in instrs[i,In] \/ t in instrs[i,Out] ]) | t in temp_t ];

constraint forall( i in instr_t)(

alldifferent( [ reg[t] | t in temp_t where i <= death[t] /\ def[t] < i ] )

);

Something like a finally tagless style encoding of block? But I’d also like the same of insn Side effectful functions? Ok. So I want

predicate block(string : name, set[temp_t] : ins, set of [temp_t] : outs, array[int] of insn : data, array[int of insns : data] : ctrl)

@dataclass

class Block:

name: str

ins: List["RegSort"]

prog: Prog

outs: List["RegSort"]

# operation = (name, out, ins)

run(prog)

def peephole(prog):

out_prog = []

for op, out, in_ops in prog:

if op == "mov" and len(in_ops) == 1 and in_ops[0] == out: # fuse out redundant movs

continue

out_prog.append((op, out, in_ops))

#[(op,outs, ins)]

Expr = Tuple[Op, Any]

def simp(expr):

def isel_stmt(stmt):

def isel_expr(expr):

match expr:

case ("add", x, y):

case ("mul", x, y):

case ("neg", x):

case ("load", x):

def eval(env, block):

for (op, outs, ins) in reversed(block):

pass