Computational Category Theory in Python II: Numpy for FinVect

Linear algebra seems to be the place where any energy you put in to learning it seems to pay off massively in understanding other subjects and applications. It is the beating heart of numerical computing. I can’t find the words to overstate the importance of linear algebra.

Here’s some examples:

- Least Squares Fitting - Goddamn is this one useful.

- Quadratic optimization problems

- Partial Differential Equations - Heat equations, electricity and magnetism, elasticity, fluid flow. Differential equations can be approximated as finite difference matrices acting on vectors representing the functions you’re solving for.

- Linear Dynamical systems - Solving, frequency analysis, control, estimation, stability

- Signals - Filtering, Fourier transforms

- Quantum mechanics - Eigenvalues for energy, evolving in time, perturbation theory

- Probability - Transition matrices, eigenvectors for steady state distributions.

- Multidimensional Gaussian integrals - A canonical model in quantum mechanics and probability because they are solvable in closed form. Gaussian integrals are linear algebra in disguise. Their solution is describable in terms of the matrices and vectors in the exponent. More on this another day.

Where does category theory come in to this?

On one side, exploring what categorical constructions mean concretely and computationally in linear algebra land helps explain the category theory. I personally feel very comfortable with linear algebra. Matrices make me feel good and safe and warm and fuzzy. You may or may not feel the same way depending on your background.

In particular, understanding what the categorical notion of a pullback means in the context of matrices is the first time the concept clicked for me thanks to discussions with James Fairbanks and Evan Patterson.

But the other direction is important too. A categorical interface to numpy has the promise of making certain problems easier to express and solve. It gives new tools for thought and programming. The thing that seems the most enticing to me about the categorical approach to linear algebra is that it gives you a flexible language to discuss gluing together rectangular subpieces of a numerical linear algebra problem and it gives a high level algebra for manipulating this gluing. Down this road seems to be an actionable, applicable, computational, constructible example of open systems.

Given how important linear algebra is, given that I’ve been tinkering and solving problems (PDEs, fitting problems, control problems, boundary value problems, probabilistic dynamics, yada yada ) using numpy/scipy for 10 years now and given that I actually have a natural reluctance towards inscrutable mathematics for its own sake, I hope that lends some credence to when I say that there really is something here with this category theory business.

It frankly boggles my mind that these implementations aren’t available somewhere already! GAH!

Uh oh. I’m foaming. I need to take my pills now.

FinVect

The objects in the category FinVect are the vector spaces. We can represent a vector space by its dimensionality n (an integer). The morphisms are linear maps which are represented by numpy matrices. ndarray.shape basically tells you what are the domain and codomain of the morphism. We can get a lot of mileage by subclassing ndarray to make our FinVect morphisms. Composition is matrix multiplication (which is associative) and identity morphisms are identity matrices. We’ve checked our category theory boxes.

import numpy as np

import scipy

import scipy.linalg

# https://docs.scipy.org/doc/numpy/user/basics.subclassing.html

class FinVect(np.ndarray):

def __new__(cls, input_array, info=None):

# Input array is an already formed ndarray instance

# We first cast to be our class type

obj = np.asarray(input_array).view(cls)

assert(len(obj.shape) == 2) # should be matrix

# add the new attribute to the created instance

# Finally, we must return the newly created object:

return obj

@property

def dom(self):

''' returns the domain of the morphism. This is the number of columns of the matrix'''

return self.shape[1]

@property

def cod(self):

''' returns the codomain of the morphism. This is the numer of rows of the matrix'''

return self.shape[0]

def idd(n):

''' The identity morphism is the identity matrix. Isn't that nice? '''

return FinVect(np.eye(n))

def compose(f,g):

''' Morphism composition is matrix multiplication. Isn't that nice?'''

return f @ g

A part of the flavor of category theory comes from taking the focus away from the objects and putting focus on the morphisms.

One does not typically speak of the elements of a set, or subsets of a set in category theory. One takes the slight indirection of using the map whose image is that subset or the element in question when/if you need to talk about such things.

This actually makes a lot of sense from the perspective of numerical linear algebra. Matrices are concrete representations of linear maps. But also sometimes we use them as data structures for collections of vectors. When one wants to describe a vector subspace concretely, you can describe it either as the range of a matrix or the nullspace of a matrix. This is indeed describing a subset in terms of a mapping. In the case of the range, we are describing the subspace as all possible linear combinations of the columns $ \lambda_1 c_1 + \lambda_2 c_2 + … $ . It is a matrix mapping from the space of_ parameters_ $ \lambda$ to the subspace (1 dimension for each generator vector / column). In the case of the nullspace it is a matrix mapping from the subspace to the space of constraints (1 dimension for each equation / row).

The injectivity or surjectivity of a matrix is easily detectable as a question about its rank. These kinds of morphisms are called monomorphisms and epimorphisms respectively. They are characterized by whether you can “divide” out by the morphism on the left or on the right. In linear algebra terms, whether there is a left or right inverse to these possibly rectangular, possibly ill-posed matrices. I personally can never remember which is which (surf/ing, left/right, mono/epi) without careful thought, but then again I’m an ape.

def monic(self):

''' Is mapping injective.

In other words, maps every incoming vector to distinct outgoing vector.

In other words, are the columns independent.

In other words, does `self @ g == self @ f` imply `g == f` forall g,f

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monomorphism '''

return np.linalg.matrix_rank(self) == self.dom

def epic(self):

''' is mapping surjective? '''

return np.linalg.matrix_rank(self) == self.cod

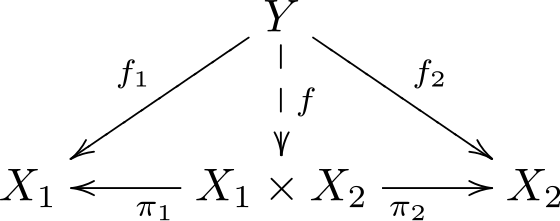

Some categorical constructions are very simple structural transformation that correspond to merely stacking matrices, shuffling elements, or taking transposes. The product and coproduct are examples of this. The product is an operation that takes in 2 objects and returns a new object, two projections $ \pi_1$ $ \pi_2$ and a function implementing the universal property that constructs $ f$ from $ f_1 f_2$.

The diagram for a product

The diagram for a product

Here is the corresponding python program. The matrix e (called f in the diagram. Sorry about mixed conventions. ) is the unique morphism that makes those triangles commute, which is checked numerically in the assert statements.

def product(a,b):

''' The product takes in two object (dimensions) a,b and outputs a new dimension d , two projection morphsisms

and a universal morphism.

The "product" dimension is the sum of the individual dimensions (funky, huh?)

'''

d = a + b # new object

p1 = FinVect(np.hstack( [np.eye(a) , np.zeros((a,b))] ))

p2 = FinVect(np.hstack( [np.zeros((b,a)), np.eye(b) ] ))

def univ(f,g):

assert(f.dom == g.dom) # look at diagram. The domains of f and g must match

e = np.vstack(f,g)

# postconditions. True by construction.

assert( np.allclose(p1 @ e , f )) # triangle condition 1

assert( np.allclose(p2 @ e , g ) ) # triangle condition 2

return e

return d, p1, p2, univ

The coproduct proceeds very similarly. Give it a shot. The coproduct is more similar to the product in FinVect than it is in FinSet.

The initial and terminal objects are 0 dimensional vector spaces. Again, these are more similar to each other in FinVect than they are in FinSet. A matrix with one dimension as 0 really is unique. You have no choice for entries.

def terminal():

''' terminal object has unique morphism to it '''

return 0, lambda x : FinVect(np.ones((0, x)))

def initial():

''' the initial object has a unique morphism from it

The initial and final object are the same in FinVect'''

return 0, lambda x : FinVect(np.ones((x, 0)))

Where the real meat and potatoes lives is in the pullback, pushout, equalizer, and co-equalizer. These are the categorical constructions that hold equation solving capabilities. There is a really nice explanation of the concept of a pullback and the other above constructions here .

Vector subspaces can be described as the range of the matrix or the nullspace of a matrix. These representations are dual to each other in some sense. $ RN=0$. Converting from one representation to the other is a nontrivial operation.

In addition to thinking of these constructions as solving equations, you can also think of a pullback/equalizer as converting a nullspace representation of a subspace into a range representation of a subspace and the coequalizer/pushout as converting the range representation into a nullspace representation.

The actual heart of the computation lies in the scipy routine null_space and orth. Under the hood these use an SVD decomposition, which seems like the most reasonable numerical approach to questions about nullspaces. (An aside: nullspaces are not a very numerical question. The dimensionality of a nullspace of a collection of vectors is pretty sensitive to perturbations. This may or may not be an issue. Not sure. )

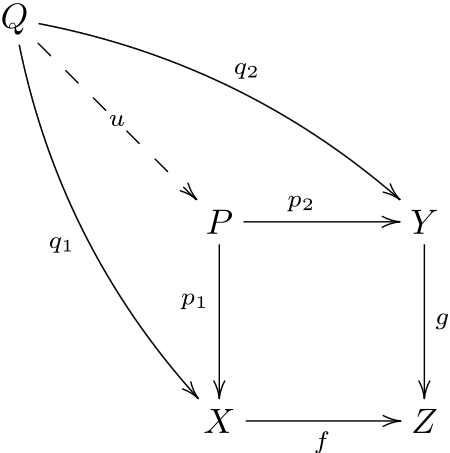

Let’s talk about how to implement the pullback. The input is the two morphisms f and g. The output is an object P, two projections p1 p2, and a universal property function that given q1 q2 constructs u. This all seems very similar to the product. The extra feature is that the squares are required to commute, which corresponds to the equation $ f p_1 = g p_2 $ and is checked in assert statements in the code. This is the equation that is being solved. Computationally this is done by embedding this equation into a nullspace calculation $ \begin{bmatrix} F & -G \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} x \ y \end{bmatrix} = 0$. The universal morphism is calculated by projecting q1 and q2 onto the calculated orthogonal basis for the nullspace. Because q1 and q2 are required to be in a commuting square with f and g by hypothesis, their columns live in the nullspace of the FG stacked matrix. There is extra discussion with James and Evan and some nice derivations as mentioned before here

def pullback(f,g):

assert( f.cod == g.cod ) # Most have common codomain

# horizontally stack the two operations.

null = scipy.linalg.null_space( np.hstack([f,-g]) )

d = null.shape[1] # dimension object of corner of pullback

p1 = FinVect(null[:f.dom, :])

p2 = FinVect(null[f.dom:, :])

def univ(q1,q2):

# preconditions

assert(q1.dom == q2.dom )

assert( np.allclose(f @ q1 , g @ q2 ) ) # given a new square. This means u,v have to inject into the nullspace

u = null.T @ np.vstack([q1,q2]) # calculate universal morphism == p1 @ u + p2 @ v

# postcondition

assert( np.allclose(p1 @ u, q1 )) # verify triangle 1

assert( np.allclose(p2 @ u, q2 ) ) # verify triangle 2

return u

# postcondition

assert( np.allclose( f @ p1, g @ p2 ) ) # These projections form a commutative square.

return d, p1, p2, univ

The equalizer, coequalizer, and pushout can all be calculated similarly. A nice exercise for the reader (AKA I’m lazy)!

Thoughts

I think there are already some things here for you to chew on. Certainly a lot of polish and filling out of the combinators is required.

I am acutely aware that I haven’t shown any of this being used. So I’ve only shown the side where the construction helps teach us category theory and not entirely fulfilled the lofty promises I set in the intro. I only have finite endurance. I’m sure the other direction, where this helps us formulate problems, will show up on this blog at some point. For what I’m thinking, it will be something like this post http://www.philipzucker.com/linear-relation-algebra-of-circuits-with-hmatrix/ but in a different pullback-y style. Mix together FinSet and FinVect. Something something decorated cospans? https://arxiv.org/abs/1609.05382

One important thing is we really need to extend this to affine maps rather than linear maps (affine maps allow an offset $ y = Ax + b$. This is important for applications. The canonical linear algebra problem is $ Ax=b$ which we haven’t yet shown how to represent.

One common approach to embed the affine case in the linear case is to use homogenous coordinates. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homogeneous_coordinates.

Alternatively, we could make a new python class FinAff that just holds the b vector as a separate field. Which approach will be more elegant is not clear to me at the moment.

Another very enticing implementation on the horizon is a nice wrapper for compositionally calculating gaussian integrals + linear delta functions. Gaussian integrals + delta functions are solved by basically a minimization problem over the exponent. I believe this can be formulated by describing the linear subspace we are in as a span over the input and output variables, associating a quadratic form with the vertex of the span. You’ll see.

References

- Rydeheard and Burstall - Computational Category Theory http://www.cs.man.ac.uk/~david/categories/book/book.pdf

- Again, thanks to Evan and James https://github.com/epatters/Catlab.jl/issues/87#issuecomment-596166224

- Artwork courtesy of David

- https://ncatlab.org/nlab/show/Vect

- https://www.cs.ox.ac.uk/files/4551/cqm-notes.pdf

- https://www.math3ma.com/blog/limits-and-colimits-part-3

- https://bartoszmilewski.com/2015/04/15/limits-and-colimits/

Blah Blah Blah

Whenever I write a post, I just let it flow, because I am entranced by the sound of my own keyboard clackin’. But it would deeply surprise me if you are as equally entranced, so I take sections out that are just musings and not really on the main point. So let’s toss em down here if you’re interested.

I like to draw little schematic matrices sometimes so I can visually see with dimensions match with which dimensions.

Making the objects just the dimension is a structural approach and you could make other choices. It may also make sense to not necessarily identify two vector spaces of the same dimensionality. It is nonsensical to consider a vector of dog’s nose qualities to be interchangeable with a vector of rocket ship just because they both have dimensionality 7.

High Level Linear Algebra

Linear algebra already has some powerful high level abstractions in common use.

Numpy indexing and broadcasting can sometimes be a little cryptic, but it is also very, very powerful. You gain both concision and speed.

Matrix notation is the most commonly used “pointfree” notation in the world. Indexful expressions can be very useful, but the calculus of matrices lets us use intuition built about algebraic manipulation of ordinary numbers to manipulate large systems of equations in a high level way. There are simple rules governing matrix inverse, transpose, addition, multiplication, identity.

Another powerful notion in linear algebra is that of block matrices. Block matrices are the standard high level notation to talk about subpieces of a numerical linear algebra problem. For example, you might be solving the heat equation on two hunks of metal attached at a joint. It is natural to consider this system in block form with the off diagonal blocks corresponding to the coupling of the two hunks. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domain_decomposition_methods

One does not typically speak of the elements of a set, or subsets of a set in category theory. One takes the slight indirection of using the map whose image is that subset or the element in question when/if you need to talk about such things. This pays off in a couple ways. There is a nice minimalism in that you don’t need a whole new entity (python class, data structure, what have you) when you already have morphisms lying around. More importantly though the algebraic properties of what it means to be an element or subset are more clearly stated and manipulated in this form. On the flipside, given that we often return to subset or element based thinking when we’re confused or explaining something to a beginner shows that I think it is a somewhat difficult game to play.

The analogy is that a beginner will often write for loops for a numpy calculation that an expert knows how to write more concisely and efficiently using broadcasting and vectorization. And sometimes the expert just can’t figure out how to vectorize some complicated construction and defeatedly writes the dirty feeling for loop.

What about in a language where the for loops are fast, like Julia? Then isn’t the for loop version just plain better, since any beginner can read and write it and it runs fast too? Yes, I think learning some high level notation or interface is a harder sell here. Nevertheless, there is utility. High level formulations enable optimizing compilers to do fancier things. They open up opportunities for parallelism. They aid reasoning about code. See query optimization for databases. Succinctness is surprising virtue in and of itself.

Aaron Hsu (who is an APL_ beast_) said something that has stuck with me. APL has a reputation for being incredibly unscrutable. It uses characters you can’t type, each of which is a complex operation on arrays. It is the epitome of concision. A single word in APL is an entire subroutine. A single sentence is a program. He says that being able to fit your entire huge program on a single screen puts you in a different domain of memory and mindspace. That it is worth the inscrutability because once trained, you can hold everything in your extended mind at once. Sometimes I feel when I’m writing stuff down on paper that it is an extension of my mind, that it is part of my short term memory. So too the computer screen. I’m not on board for APL yet, but food for thought ya know?

Differences between the pure mathematical perspective of Linear Algebra, and the Applied/Numerical Linear Alegbra

I think there a couple conceptual points of disconnect between the purely mathematical conception of vector spaces and the applied numerical perspective.

First off, the numerical world is by and large focused on full rank square matrices. The canonical problem is solving the matrix equation $ Ax=b$ for the unknown vector x. If the matrix isn’t full rank or square, we find some way to make it square and full rank.

The mathematical world is more fixated on the concept of a vector subspace, which is a set of vectors.

It is actually extremely remarkable and I invite you for a moment to contemplate that a vector subspace over the real numbers is a very very big set. Completely infinite. And yet it is tractable because it is generated by only a finite number of vectors, which we can concretely manipulate.

Ok. Here’s another thing. I am perfectly willing to pretend unless I’m being extra careful that machine floats are real numbers. This makes some mathematicians vomit blood. I’ve seen it. Cody gave me quite a look. Floats upon closer inspection are not at all the mathematical real numbers though. They’re countable first off.

From a mathematical perspective, many people are interested in precise vector arithmetic, which requires going to somewhat unusual fields. Finite fields are discrete mathematical objects that just so happen to actually have a division operation like the rationals or reals. Quite the miracle. In pure mathematics they more often do linear algebra over these things rather than the rationals or reals.

The finite basis theorem. This was brought up in conversation as a basic result in linear algebra. I’m not sure I’d ever even heard of it. It is so far from my conceptualization of these things.

Monoidal Products

The direct sum of matrices is represented by taking the block diagonal. It is a monoidal product on FinVect. Monoidal products are binary operations on morphisms in a category that play nice with it in certain ways. For example, the direct sum of two identity matrices is also an identity matrix.

The kronecker product is another useful piece of FinVect. It is a second monoidal product on the catgeory FinVect It is useful for probability and quantum mechanics. When you take the pair of the pieces of state to make a combined state, you

def par(f,g):

''' One choice of monoidal product is the direct sum '''

r, c = f.shape

rg, cg = g.shape

return Vect(np.block( [ [f , np.zeros((r,cg))] ,

[np.zeros((rg,c)) , g ]] ))

def par2(f,g):

''' another choice is the kroncker product'''

return np.kron(f,g)

We think about row vectors as being matrices where the number of columns is 1 or column vectors as being matrices where the number of rows is 1. This can be considered as a mapping from/to the 1 dimensional vector. These morphisms are points.

The traditional focus of category theory in linear algebra has been on the kronecker product, string diagrams as quantum circuits/ penrose notation, and applications to quantum mechanics.

However, the direct sum structure and the limit/co-limit structures of FinVect are very interesting and more applicable to everyday engineering. I associate bringing more focus to this angle with John Baez’s group and his collaborators.

Anyway, that is enough blithering.